How Nonprofits Can Truly Advance Change

by Hildy Gottlieb | NP Quarterly | 1.25.22

Click for link to original article.

What would it take for the nonprofit sector to live up to its potential to advance systemic social change?

In the 30 years I’ve been part of this sector, that question has been a constant. Critics often focus on the sector’s size—a huge asset that could be leveraged for more significant change. In the US alone, the nonprofit sector raised $471 billion in donor revenues last year for 1.3 million organizations employing 12 million people. Changemakers themselves often feel like Sisyphus, pushing a boulder uphill, only to see it roll back down.

Everyone seems to have their pet answer. More diverse boards. More equitable funding. Reforming human resources. Or evaluation. Or leadership.

It’s time to acknowledge that there is not one silver bullet that will lead to our potential. What is needed is structural change in every aspect of nonprofit work. And the time for that change is right now.

What’s Been Tried

The quest to enhance nonprofit results is not new. Below are just a few reforms I have witnessed.

Enhancing board effectiveness: The baseline for boards is the seemingly official list of roles and responsibilities (few of which are actually law, just “best” practice). Governance reforms like governance as leadership and policy governance have recently been joined by new models to flatten organizations with distributed leadership (e.g., holacracy and sociocracy), as well as others built around circles, committees, roles, and/or community engagement.

Better fundraising: “Not enough results” is often equated with “not enough money.” For years, those tasked with raising money have been steeped in donor-centered fundraising, assisted by software programs that turn people into acronyms like LYBUNTs (gave Last Year But Unfortunately Not This year).

Social entrepreneurship: The trend toward social entrepreneurship also comes from the search for sustainable funds. Before social enterprise there was the “run like a business” trend—a trope that continues to tout the benefits of business approaches.

Foundation-favored reforms: Foundations are often the source of organizational reforms. Decades ago, it was metrics and logic models—requiring “evidence” that short term funding of one nonprofit would somehow make a dent in addressing large-scale social problems. Around the same time, foundations began requiring collaboration as a condition for getting funded, the precursor to the collective impact and impact philanthropy movements.

Bang for the buck: Even accounting has not been immune to fads. The drive to hold organizations to a standardized (and very low) ratio of indirect funds compared to direct program funds, has now seen the pendulum swing, where the very people who sought to limit investment in overhead have confessed they were mistaken.

That mea culpa is sadly all too rare. More often, when these experiments fail to create the intended improvement in communities, those failed efforts live on, with many of them eventually canonized as “best practice.”

Why These Fixes Haven’t Worked

Albert Einstein famously noted, “No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it.” And yet that is exactly what we keep doing: generating new things to do, without changing the assumptions—our level of consciousness—behind all that doing.

What, then, are the assumptions at the heart of all these reforms?

- Organizations at the center: Perhaps the foremost assumption is that organizations are the unit of primary importance. In the beginning, “charity” was the realm of individual churches and private philanthropists. Each of those efforts was owned by its founding philanthropist or religious order, just as modern-day programs are owned by a nonprofit, a social entrepreneur, a church, or a government department. That translates into legal fiduciary duties of care and loyalty—not to the community, but to the organization.

That primacy of individual organizations is a huge barrier to creating equitable, healthy communities. Over 40 years ago, Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward summarized this in their seminal work, Poor People’s Movements. They observed that too often organizations actually undermine the social movements they were founded to support, “abandoning their oppositional politics…becoming increasingly subservient to those on whom they depend.”1

- Imitating the cause of social problems: Many day-to-day nonprofit functions have been adopted from places of power and privilege. For example, strategic planning originated in the military before being adopted by the business world, and then by nonprofits. This leads to win/lose, zero-sum strategies aimed at short-term goals—the opposite of what is needed to create change.

Modeled after the work of the early philanthropists, who modeled their own efforts on religious charity, modern-day social programs emphasize alleviating the suffering of one deserving person or group at a time, rather than the kinds of transformative change that might threaten the standing of powerful individuals and groups.

Accounting, human resources, and other seemingly invisible functions we take for granted as “just the way it’s done” have been copied and pasted directly from the business world. These business origins emphasize sustaining the capacity of the organization rather than sustaining the community, fostering a culture of competition rather than cooperation.

It is therefore not just how groups raise money or how work is done “out there” in the community that stops change from happening. It is that internal work, grounded in the profit mandate, in military strategy, and in religious ideas of deservedness, that stops us before we even get out the door. From there, when nonprofit leaders take university classes in nonprofit management or engage in other capacity building interventions, those leaders are then taught these “best practices” as “the right way” to do their work.

When the tools used by social change groups are lifted wholesale from the very institutions that have caused so much injustice in the first place, then even those seemingly mundane internal functions end up perpetuating the very conditions those groups are seeking to change.

It is important to note that these functions are not broken. They are doing exactly what they were built to do. They are simply the wrong tools for the job. Reforming a hammer because it does a lousy job of opening a wine bottle cannot turn that hammer into a corkscrew. In a paper published in the Academy of Management, Dr. Steven Kerr described this phenomenon as “The Folly of Rewarding A, While Hoping for B.”2 Enough said.

- Fixing what is wrong vs. creating what is right: One final reason nonprofit and philanthropic reforms have failed to create meaningful change is because they are aimed at fixing what is perceived as the problem, rather than creating what is possible. To create structures and systems that will lead to change, the focus must reach beyond problem-solving; what is required is a social change ecosystem where means reflect desired end results.

What Will Work

Progressive social change happens when people make decisions and take collective action about the issues in their own lives. The following explores what some nonprofit systems might look like if they were rooted in values of equity, relationship, trust, enoughness, and possibility.

Organizational structure and leadership: If social change organizations reflected the world we want to see, relationships within organizations would resemble communities and natural ecosystems—networks of mutual support committed to a shared vision and shared values. This is how social movements organize—and when they succeed that is the heart of their success. Organizational “walls” would be porous, fostering an open flow of ideas, people, and resources from outside those “walls.”

People from affected communities would be seen as leaders of their own change, with organizations actively helping to develop those leaders. Power and decision-making would be centered in those community leaders, with organizational staff taking a support role. Where required by law or regulation, boards would see themselves as a support to all those individuals—not as leaders.

Planning and program design: To create a more equitable, humane future, community members would determine goals and plans for their communities. The planning process itself would be mindful of privilege, patriarchy, colonialism, and racism that are often present in planning processes—including decisions about who is invited to whose table, and who facilitates the conversation. That planning would be future-focused, aimed at dramatic, visionary results as an achievable goal. From there, programs would be designed by community members, building on their existing strengths, and assisted by organizational staff only as needed.

Evaluation as learning: If evaluation aligned with the world we want to see, those reflections would be shared across the community and throughout whole fields of work—learnings from one food bank shared with all food banks everywhere, for example. Because humans learn through stories, learning and evaluation would center stories of the relationships that created the change, seeing quantitative data as just one way to illustrate those stories. That learning would therefore be a powerful, open-source, shared effort, funded commensurate with its importance.

Communication and engagement: To support community members in their change efforts, the goal of communication would be to build collective strength towards accomplishing the community’s goals. Those activities would emphasize all that we can accomplish together as allies, that none of us can accomplish on our own, instead of the marketing mandate to differentiate and compete.

Accounting and accountability: With this emphasis on co-creating change, an organization’s foremost accountability and stewardship would be to the people the nonprofit supports.3 Duties of care and loyalty, if still legally aimed at care for and loyalty to the organization, would be interpreted as possible only if the organization is upholding its primary accountability to the community.

Human resources and compensation: Similarly, the work of human resources would be to live up to its name—providing the resources humans need to be their best. Creating conditions for employees’ success would include compensation that reflects the value of that work. Such compensation would be adequate for employees to not worry about finances, freeing staff to be at their best both at work and at home.4

Resourcing and funding systems: Lastly, the one place everyone seems to focus their reform efforts—resources. If an organization’s vision and values include people being valued for who they are rather than their monetary wealth, resourcing social change must reflect those values. Those efforts—rooted in sharing, relationship, equity, and trust—would reflect the stone-soup spirit of collective enoughness,5 that together we have everything we need. In-kind resources and volunteers would therefore be valued more than cash, as those in-kind gifts are the actual resources that are needed.

Most importantly, valuing people and community over money would mean a significant shift in the role of foundations. Rather than self-appointed arbiters of what change deserves support, the role of foundations would be to ensure that there are adequate funds to accomplish what communities determine they need. Expecting community groups with expertise in literacy or homelessness to also acquire expertise in fundraising, when foundations’ raison d’être is money, is one more example of the folly of rewarding A when what we want is B.

The Time is Now

In The Way Out: How to Overcome Toxic Polarization, Columbia University professor Peter Coleman notes, “Studies have shown that enduring patterns often become more susceptible to change after some type of major shock destabilizes them.” Between COVID, George Floyd’s murder, the climate crisis, and the January 6th insurrection, destabilizing shocks are evident everywhere we turn.

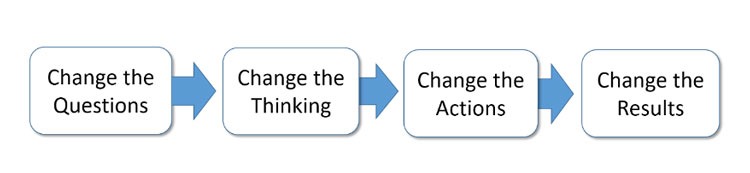

If ever there were a time when the nonprofit sector was ripe for transformation, it is now. And that transformation will start by asking and answering different questions about every aspect of our work.

Begin by asking the following questions:

1) What actually creates change?

Nonprofits often pretend that they know how to, for example, end hunger and poverty, ensure literacy, and create social justice. However, given that those problems are still with us, we would be wise to heed Einstein’s suggestion and change the assumptions that guide the work of social change. This will require replacing the role of “expert” with a spirit of humility and approaches rooted in inquiry, listening, and learning.

2) As a nonprofit organization, what might our role be in supporting change (rather than leading change)?

- What efforts are underway among real people in your community? (If you think the answer is “not much,” keep looking. You’ll be amazed at what you find.)

- What do your community members really want? Have you asked them about the future they aspire to live in? Or do you only ask about problems and needs, seeing them as deficits in need of saving?

- What roles are needed to support those efforts, that your organization is capable of filling? How might you leverage your access to people and resources in support of those community-driven efforts (instead of seeking to lead those efforts)?

3) What would alignment look like?

To create what is possible, first cause no harm. Seemingly benign functions like accounting and human resources too often block change. Ask: What ways of doing this task would reflect our community’s dreams for its future?

4) Ask funders to do the same.

In The Revolution Will Not be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex, Amara H. Pérez notes, “Foundation funding…not only exhausts us and potentially compromises our radical edge; it also has us persuaded that we cannot do our work without their money and without their systems.” 6 While nonprofit leaders often feel powerless in the face of foundations who hold access to funding, anyone has the power to invite a different conversation by asking different questions—the power to set the table, not just wait to be invited to “the” table.

- Nonprofit leaders can decide not to compete, asking funders: “We don’t want to compete. Who else is working on this? Will you fund us all?”

- Nonprofit leaders can decide what compensation is equitable, asking funders: “We intend to pay wages worthy of the work people do. What would it take for you to make that possible—not just for us, but for everyone you fund?”

- Nonprofit leaders can decide to value community members for their own work, asking funders: “We are working closely with our community members as leaders of their own change. How will you ensure we can pay them for their time and expertise?”

These questions assume that community members and the organizations that support them can make their own decisions—that communities, not funders, have the right to design their own futures.

Conclusion

Stepping into our potential to create more visionary change in the world will require significant changes in every aspect of work in the nonprofit arena. And because change happens via collective action by real people, perhaps the most important question we can ask is this: If it winds up that what must change is us, are we willing to make that change?

1. Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward, Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail. 1977, Vintage Books (Random House), page xxi.

2. Steven Kerr, “On the Folly of Rewarding A, While Hoping for B.” Academy of Management Journal, December 1975. https://www.ou.edu/russell/UGcomp/Kerr.pdf

3. For details about what this might look like for accountability, see Hildy Gottlieb, “The Fact-based Fallacy of Accountability to Donors.” Community-Centric Fundraising, April 26, 2021. https://communitycentricfundraising.org/2021/04/26/the-fact-based-fallacy-of-accountability-to-donors/

4. One of the biggest advocates for a livable minimum wage is Dan Price, CEO of the for-profit company, Gravity Payments. https://www.businessinsider.com/gravity-payments-dan-price-ceo-raise-minimum-wage-revenue-2021-8 Recently the nonprofit Choose 180 has been highlighted for taking the same approach. https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/labor-shortage-or-living-wage-shortage-one-king-county-nonprofit-is-taking-a-different-approach/

5. The term “Collective Enoughness” is explained with examples in this article at Stanford Social Innovation Review: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/creating_a_better_world_means_asking_better_questions.

6. Amara H. Pérez, Sisters in Action for Power, “Between Radical Theory and Community Praxis: Reflections on Organizing and the Non-Profit Industrial Complex.” In The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex, edited by INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence. 2007, South End Press, page 98.